Several years ago now, a sixteen-card game took the tabletop gaming world by storm. Everyone seemed to fall in love with Love Letter, the light game of bluff and deduction. Multiple versions were released, and even upgraded editions with larger (and more) cards and nicer tokens of affection.

Curios feels a lot to me like Love Letter. It, too, is a small game of light bluff and deduction with few components that plays very quickly. And like Love Letter before it, I just don’t like it very much.

Before I begin to explain why–which aligns pretty closely with the tepid review I gave Love Letter–I should note that I appear to be in the minority on this one. The comments on Board Game Geek and from other reviewers tout its “rich” gameplay and “good decisions.” Tom Vasel of the Dice Tower has given it his seal of approval. The BGG average score from players is 6.7–not tremendous, but no slouch, either. It gives me no pleasure to disagree with these comments and ratings, but I really don’t get the love for Curios.

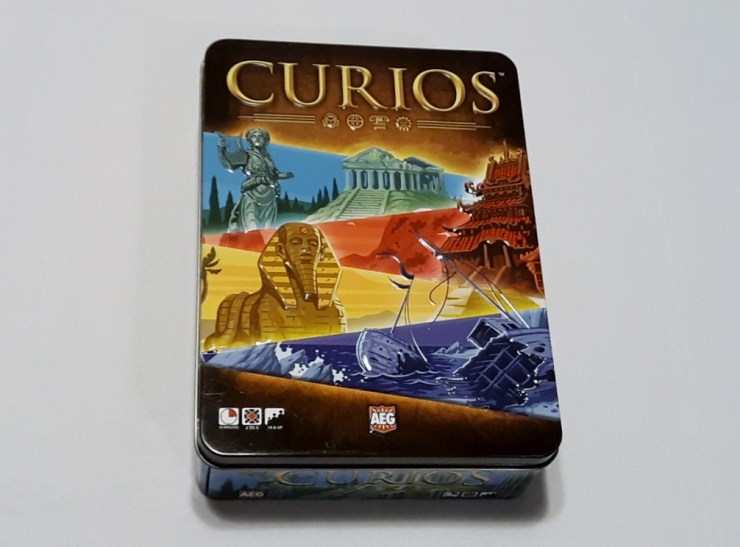

The components indicate that the publisher believes in this game. Rather than beginning with what could be very basic components that fit in a standard small-size game box, Curios comes in a deluxe tin with nice artwork, chunky gems, and a fancy metal lantern just to mark who goes first. The pawns are nothing special, but they get the job done and are nicer than cubes on tiny cards. The tin is bigger than I’d want, but it does hold everything nicely and gives the impression that this game is worth noticing. The colors for the artifacts and sites need a little explanation, yet all told, this looks like a lavish production for a small game.

But the gameplay, to me, is just boring.

The goal of the game, as in many, is to get the most points, and you do this by collecting artifacts of different types. Each type has a value of 1, 3, 5, or 7. You don’t know the values of the artifact cards, but you do have cards in your hand that, as in Clue, tell you what the value is not. If you’re holding the 7-value card for the Colosseum, you know for certain that the Colosseum artifacts are worth 1, 3, or 5 points.

On a turn, you’ll place the pawns of your color on the different artifact sites. The first person to place there places 1 pawn to get an artifact, the second 2 pawns, and so on. Once all players have either placed all their pawns or have nowhere else they can place, the round ends, and whoever placed the most pawns on each artifact site gets a free artifact of that type.

Before the next round begins, players may reveal one of their cards, giving the other players precious information in exchange for taking another pawn of their color, potentially opening more possibilities in the next round. To me, this is the most compelling decision in the game. The information economy (as you will see below) is high on speculation and low on certainty. Is it worth it to potentially get more artifacts, or is it better to keep your cards close to the vest?

Rounds continue until two or more artifact sites are empty. Then the real values are revealed, each artifact is worth its value, and the player who has the most points wins.

Curios works from a mechanical standpoint. The idea of placing pawns on a site, of trying to get the highest-valued stuff, of having limited information–all of this makes sense. It isn’t broken. It’s simple to explain, simple to play, and not taxing in the least. And it’s that last point that, I think, is my main issue with the game–because it isn’t taxing in the least, it’s not really all that fun.

While there’s certainly a place for simple and breezy games–a player in one of my games said, “This would be good for late at night when you’re too tired to think”–Curios feels a little too simple, a little too breezy to be worth the time. The idea behind the game is that players are trying to deduce the value of the artifacts and collect the ones that have the highest value, but in my experience, deduction won’t take you very far, or at least not as far as it should.

Let’s say you’re playing a three-player game and have four cards in your hand. That’s four pieces of information you know that no one else does. Based on the cards in hand, you’ve narrowed down the value of the purple gems to 1 or 7. Until another player either reveals a card or makes a move, you have a 50-50 shot of striking big or striking out.

This, I suppose, is where bluff comes in: a player holding the 7 might try to lure other players there, knowing that the value is not the highest. But how does that player know the value isn’t 5? Or that by placing there, they aren’t losing out on a much greater prize? Or maybe a player goes to the purple because they don’t know anything but know that green has a low value, which leads the other players astray. Or maybe a player chooses purple because that’s the only place they can go.

Basically, my problem is that the only reliable information is what you can see–either cards in your hand or cards played on the table–and these deductions so simple they aren’t interesting. And the other information–based on inferences from player behavior–are unreliable to the point of being (almost) meaningless.

I think the reason why the deductions from player behavior feel meaningless is the pawn economy in the game. Players have a limited number of pawns to work with, and the costs for each site escalate as more players choose to go there. In a single round, I usually have one play where I choose which artifact I really think is valuable; the rest of my plays are dictated by which spaces are available given the pawns I have left. Where do I have enough pawns to go? Where might I snag the extra artifact if I have the most? These are considerations, sure, but most of my choices feel fairly scripted. So even if I do have actionable intel, I’m forced to play a not-very-interesting resource management game with my pawns to make the best of the rest. So the signals I’m sending to other players (and the signals they’re sending to me) aren’t all that much to go on: they’re usually just signalling where they can possibly put their pawns down to get something.

Because of this, my choices don’t seem to matter all that much. For my taste, I think the game needs more certain information–maybe passing cards (so not everyone at the table has information, but you have more) or, as one of my friends suggested, ensuring that each of the four sites has a different value (1, 3, 5, or 7), allowing for more interesting deductions.

I’m okay with risk and speculation–Reiner Knizia is one of my favorite designers!–but the combination of this with the pawn management doesn’t quite work for me. It doesn’t feel as much like speculation as just moving pieces around and seeing what happens. That being said, my opinion of the game has (believe it or not) improved over my several plays with different groups. No one I’ve played it with has hated the game. And I don’t hate Curios. I wouldn’t refuse to play it if someone else wanted to. It is inoffensive. It works. But that’s about as high of praise as I can muster. And even among my friends who liked it more than I did, the consensus was “Yeah, I’d play that. I wouldn’t buy it. I probably wouldn’t suggest it.”

The reason for my tepid response is the many other great filler games already on the market. If I would like to play a short game of bluff and deduction, I would choose Werewords 100 percent of the time. If I’m in the mood for light speculation, I’d pick No Thanks. If I’m just looking for something quick and simple with some light decisions, I would choose Heul Doch! Mau Mau or The Mind , both of which have the distinction of being a lot more sociable, even funny, and are even easier to teach. If I’m looking for a light resource/hand management game, Jaipur or Pearls or Krass Kariert or Fantasy Realms are all options I’d pick first.

I like short and simple games, but the minimum bar they need to clear is, Would I rather play this than simply talking to the other people at the table? Obviously, each person will feel differently about this question–and if you like Love Letter, you probably will feel differently: I think you will enjoy Curios. For me, I’d rather enjoy light conversation than fill the time with what’s on offer here.

iSlaytheDragon would like to thank AEG for providing us with a copy of Curios for review.

-

Rating:

Pros:

Simple, quick, and inoffensive

Game works and offers light decisions that some players might enjoy

Cons:

Not much meat on the bone

Deduction doesn't get to inform placement decisions as much as you might hope

Not as much actionable intel as I want from a deduction or bluffing game

Discussion5 Comments

This looks pretty cool, but given we share the same view of Love Letter, I think I’ll pass 🙂

Curios is better than Love Letter…but not by much.

Tell us what you really think! LOL

Yeah, it doesn’t look that interesting. Thanks for suffering for us!

By the description you made of the rules, this sounds a lot like The Boss, but less interesting. In The Boss, you similarly have (Clue-style) information on how valuable the locations are, and in the end whoever bid the most on a location gets the prize. But the bidding isn’t as restrictive as Curios sounds it is, so players bidding on a location are actually sending a message (or bluffing). Also, at each of your turn, you have to reveal one of the cards you had (your info), meaning the timing of your bids is key.

That sounds much more interesting!